Shared Event-loop for Same-Origin Windows

I recently came across an article that says, All windows on the same origin share an event loop as they can synchronously communicate. This got me thinking — so if I’ve multiple tabs (since tabs are basically same as windows in modern browsers) of different pages from the same host, they all will be rendered in a single thread. But this doesn’t make sense, since Chrome runs each tab in its own process. There’s no way they could share the same event-loop. Time to dig in.

Chrome’s Process Model

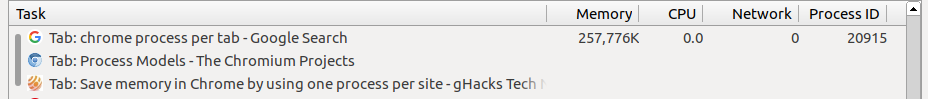

A quick test using chrome task manager proved that I was right. Each tab with same origin was indeed running in separate processes. But as I was digging through the Chrome task manager processes, I noticed a bunch of tabs that were running under the same process id. For example:

They weren’t even from the same domain. So what’s going on here? After a quick google search, it turned out that Chrome has a complex process model: chromium.org/developers/design-documents/process-models. By default, Chrome uses process-per-site-instance model, which is:

Chromium creates a renderer process for each instance of a site the user visits. This ensures that pages from different sites are rendered independently, and that separate visits to the same site are also isolated from each other. Thus, failures (e.g., renderer crashes) or heavy resource usage in one instance of a site will not affect the rest of the browser. This model is based on both the origin of the content and relationships between tabs that might script each other. As a result, two tabs may display pages that are rendered in the same process, while navigating to a cross-site page in a given tab may switch the tab’s rendering process.

But in reality I think it’s more complex that what is stated above. Ctrl+clicking different links from the same page sometimes open links in one process sometime it’s not — whatever their origin is.

Anyway, I felt the urge to test if these tabs under the same process are really sharing the same event loop. So I wrote a long running synchronous task. Guess what! It’s just an empty for loop:

function longrunning(){

for (let i=0; i<10000000000; i++);

}

Then I needed to inject this into one of these tabs-per-process. There is this nice extension called Custom JavaScript for websites that can do the trick. As I injected the script using this extension into one of the tabs and ran it, it literally hanged all the tabs in the process. Mission accomplished. I have never been so happy to see hanged pages like that.

Connected windows with synchronous communication

Back to the first article I was talking about. It also mentioned that these windows can also synchronously communicate with each other. So these tabs must be connected to each other somehow. From the article about Chrome process model:

we refer to a set of tabs with script connections to each other as a browsing instance, which also corresponds to a “unit of related browsing contexts” from the HTML5 spec. This set consists of a tab and any other tabs that it opens using Javascript code. Such tabs must be rendered in the same process to allow Javascript calls to be made between them (most commonly between pages from the same origin).

Alright, that means to have connected windows we need to open them using javascript. There are actually several ways to do this in javascript. Using, iframe, window.frames and window.open. And to communicate with each other, we can use window.postMessage web api. We can also easily test if tabs opened with window.open share the same event-loop. I prepared this demo page that’ll open up a popup window using window.open. Then both the top window and child window run some synchronous tasks, and we can see how they affect each other.

The demo is available here. You’ll need to allow popup to see this working. But here’s the output from the console in top.html:

[0.00] TOP: before opening popup

[0.01] TOP: after popup opened, popup window url: about:blank

[0.01] TOP: starting long synchronous process. This will prevent loading and parsing of popup window

[4.93] TOP: finished long synchronous process.

[4.93] TOP: adding 1s timeout.

[5.82] CHILD: starting long synchronous process inside popup window. This will prevent the event loop in top window

[10.79] CHILD: finished long synchronous process inside popup window.

[11.15] CHILD: popup initial html loaded, popup window url: http://localhost:4000/assets/chrome-process-models/child.html

[11.18] TOP: timed out

You can see the total elapsed time in seconds in square brackets for each event. TOP indicates it’s logged from the parent window and CHILD indicates it is logged from the popup window. Here is a rundown of what’s happening:

Opening the popup window is synchronous but the content in the popup is loaded asynchronously. That’s why when we inspect the popup url right after

window.open, it is set toabout:blank. The actual fetching of the URL is deferred and starts after the current script block finishes executing.Next we run a long running task in the top window. This blocks the event loop and any pending callbacks. So the content in the popup window won’t be able to load until the synchronous process finishes.

Then we add a 1 sec timeout in the top window. This finishes the current script block in the top window. That means now the popup window will get a chance to load its content.

The popup window will start loading content and execute any javascript code it sees along the way. At the top on the content of the popup window, we again start a long running task. As long as it’s running it’ll prevent any pending callbacks from execution. That means our 1 sec timeout in the top window will also be delayed.

Next we see the

DOMContentLoadedevent is fired for the popup window. This event is fired when the initial HTML document has been completely loaded and parsed, without waiting for stylesheets, images, and subframes to finish loading.And finally we see the 1 sec timeout callback is fired approximately after 6 seconds later.

So it’s clear from the timings of when content is loaded in popup and when the setTimeout callback is fired in top window - that they both share the same event-loop.

So how do we run same-origin windows in it’s own process without affecting each others’ event-loop? It turns out we can pass an option noopener in window.open(). But using the option also loses any reference to the parent/child window. So we can’t communicate between the windows using window.postMessage().

All these behavior could be different in different browsers. It’s all actually browser implementation specific. We can even pass different flags in Chrome and choose different process model.